About 45 persons learned about the life and art of Grant Wood as actor Tom Milligan presented “Grant Wood: Prairie Rebel” at the Greene County Historical Museum Sunday afternoon.

Milligan has in his repertoire three one-man historical interpretations of Iowans. He performed “American Dreamer: The Life and Times of Henry A. Wallace” in Jefferson last fall. Milligan’s show “The Not So Quiet Librarian” is based on the life of Forrest Spaulding, director of the Des Moines Public Library from 1927 to 1952. Spaulding wrote the Library Bill of Rights which was eventually adopted by the American Library Association. According to Historical Society board member Chuck Offenburger, who served as emcee Sunday, the group hopes some time to bring that show to Greene County.

All three of Milligan’s programs were researched and written by Cynthia Mercati.

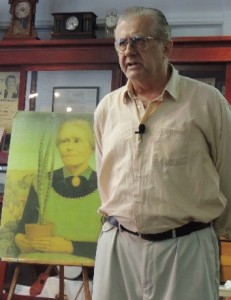

In “Prairie Rebel,” Milligan told Wood’s life story in first person, as his own. He told of the mutual disdain between he and his father, Francis Maryville Wood, and his close relationship with his mother, Hattie Weaver Wood. Wood’s earliest drawings were pictures of chickens done on scraps like empty cracker boxes with charred sticks taken from the kitchen wood stove.

Wood started art school at the Minneapolis School of Design and Handicraft after graduating from Cedar Rapids Washington High School in 1910. He didn’t finish there for financial reasons. He attended the night classes at the University of Iowa without enrolling, and quit before he ever did enroll. He next attended the Art Institute of Chicago, but didn’t finish because of money. He finally got a job teaching art at a junior high school.

He went to Paris in the summer of 1920 and studied at the Julian Academy. Between 1920 and 1928 he made four trips to Europe and painted as an Impressionist. During that time he created his gallery, 5 Turner Alley, behind a funeral home in Cedar Rapids.

The city of Cedar Rapids commissioned him to create a very large stained glass window for city hall. He traveled to Munich to research the project, and it was there that he saw the art of German and Flemish artists that eventually had the greatest influence on his work. “They were careful men who couldn’t be pushed, wouldn’t be rushed, men with an eye for detail,” Milligan/Wood said.

“When I came back to Iowa that time…I was different….My neighbors in Cedar Rapids, their homes, the clothes they wore, the patterns in their tablecloths, the tools they used, I suddenly saw all of this commonplace stuff as art, real and uncontrived… I now knew what I was supposed to paint, and why, because the usualist things are the best,” he said.

He painted his mother in “Woman With Plants” in 1929. From that time on, he knew what he would paint. “’Woman With Plants’ changed my career. ‘American Gothic’ changed my life,” he said.

Milligan/Wood told of using his dentist, Dr Byron McKeeby, and his sister Nan as his models for “American Gothic,” though the two never posed together. He told of the Stone City Art Colony which functioned in 1932 and 1933, partly to provide work for artists during the Great Depression. He told of teaching and being fired at the University of Iowa, of a disastrous marriage to singer Sara Maxon, and of depression after the death of Hattie Wood. He eventually started painting again in a small studio at Clear Lake and was later made a full professor at Iowa.

He was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and died soon after, on February 12, 1942, the day before his 51st birthday.

“Other artist may see and paint the practical beauty that is Iowa’s landscape, but Grant Wood discovered it,” Time magazine wrote after his death.

Those who attended the Sunday program were welcomed by Jeane Burk and Roger Aegerter, dressed for some version of “Greene County Gothic.”

Milligan’s performance in Jefferson was funded by a grant obtained by the Historical Society from Humanities Iowa, a nonprofit organization committed to bring the humanities to life and to the public.