Interest is high in a carbon dioxide (CO2) pipeline proposed by Summit Carbon Solutions to run diagonally through Greene County from the Louis Dreyfus ethanol plant in Grand Junction on the east side of the county to connect to a Poet ethanol plant near the southwest corner of the county.

About 75 persons attended a meeting in Jefferson Aug. 8 organized the Sierra Club Iowa chapter. Some were there to get more information about the proposal, but the prevailing sentiment, and the action sought by Sierra Club, was to strongly oppose the pipeline.

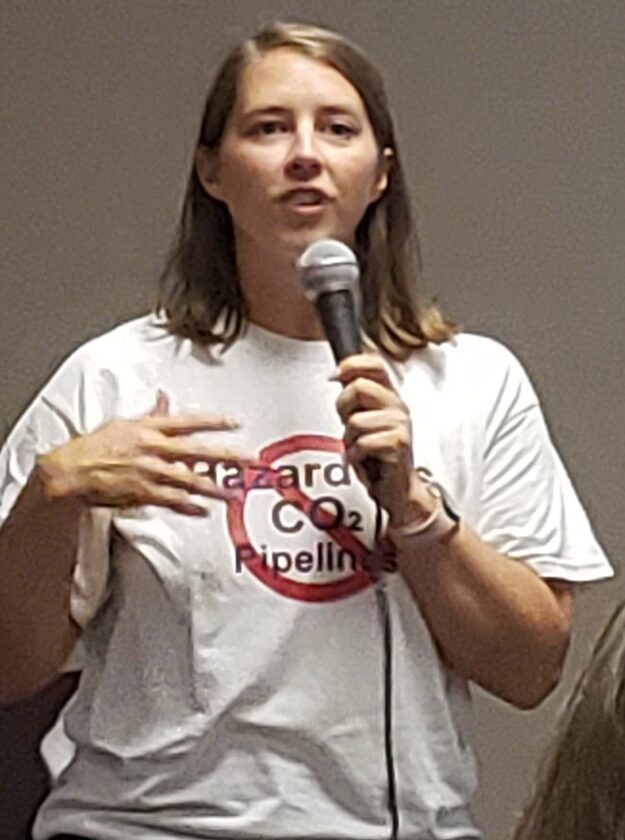

Franklin Township environmental activist Chris Henning opened the meeting by reminding attendees that the pipeline issue is bipartisan. “It’s our constitutional right, our property rights that are at stake here, besides our environment,” she said.

Summit Carbon Solutions is required to hold public information meetings in each of the 23 counties through which Phase 2 will run. (Phase 1 was initiated two years ago and is still not permitted.) Those meetings begin Aug. 26. The Sierra Club is holding meetings prior to those meetings.

James and Jan Norris of Montgomery County have been fighting Phase 1 and helped facilitate the Greene County meeting. James Norris noted that “in a divided nation, we found unification” in fighting against CO2 pipelines. He said Summit has billions of dollars to use to get both phases approved, “and the only way we’re going to beat this thing is by working together.”

Jessica Mazour, conservation program director for Sierra Club Iowa, was the primary speaker.

She presented what she called “Carbon Pipeline 101.” In a nutshell, carbon pipelines involve capturing carbon dioxide emissions, chilling the emissions to liquify them, and then moving them to deep underground storage via an underground pipeline.

Mazour said Summit’s reasons for wanting to build pipelines aren’t to slow climate change, to bolster the economic viability of ethanol production, or to provide stable aviation fuel, but to garner federal tax credits. According to Mazour, the 456Q and 45Z federal tax credits, paid per ton of carbon sequestered or used for enhanced oil recovery (fracking), would amount to $30 billion or more to Summit, leading to “wealthy people getting richer.”

She named five primary issues with CO2 pipelines: they damage the land; eminent domain should not be used for private gain; the public via the federal tax credits would be pay for a project from with private companies gain; the pipelines are dangerous; and carbon capture and storage (CCS) isn’t good for the environment or slow climate change.

•Soil compaction caused by the heavy equipment used to construct a pipeline can result in reduced crop yields for as long as six years after construction, she said, using construction of the Dakota Access pipeline as an example. Summit would have to pay three-year crop loss, but the loss would continue.

•Eminent domain is used for water lines, roads, bridges “that we all can use and need. This project is not that. It’s a private company with private investors taking public money to get rich,” Mazour said. She said that in Phase One, there are still 848 parcels for which the landowners have not signed easements. If Phase One is ultimately built with the state granting eminent domain, it would be the largest use of eminent domain in Iowa history.

“This truly is precedent-setting. We cannot let this go through or we’re giving the right to any private company to come in and take land as long as there can be some sort of claim that they’re serving the public,” Mazour said.

•She told of a CO2 pipeline rupture in Satartia, MS, in February 2020. A rupture was caused by a 7-inch rain followed by a landslide and the failure of a weld. Although the pipeline was a mile away from Satartia, more than 40 people were hospitalized, 300 persons had to be evacuated, and some people are still suffering from memory loss and other neurological issues, Mazour said.

Carbon dioxide is heaver than air, so it settles to the ground and travels through low-lying areas. It draws oxygen from the air, making gas engines useless. “We’re talking about some serious stuff, some scary stuff,” she said, noting that in Satartia residents were unable to drive away from the affected area.

CO2 can travel quickly, up to 1,300 feet in four minutes, and rural EMS and hospitals aren’t prepared to deal with such a disaster, she added.

The Pipeline and Hazardous Material Safety Administration (PHMSA) does not yet have safety rules in place because the technology is relatively new. “There is no reason we should be moving forward with anything if we don’t have basic safety rules in place. We need to slow down and stop these projects from coming,” Mazour said.

Finally, carbon pipelines harm the environment.

•The process of capturing CO2 gas, cooling it to a liquid and then pressurizing it requires an extraordinary amount of water. The ethanol plants included in Phase 1 of Summit’s plan are projected to use 3.6 billion gallons of water annually for carbon capture and storage. Adding that to the water the ethanol plants already use, the total is 13.5 billion gallons annually. The water would come from Iowa’s deep bedrock aquifers, where water has been collecting for thousands of years. It replenishes very slowly. Draining the amount of water needed for carbon capture and storage would deplete the aquifers totally within our lifetimes, Mazour said.

“It’s terrifying to know that we’re going to allow the public water that’s meant for us and our communities to get squandered on a private project that wants our money and our land and will affect our safety,” she added.

Summit must obtain water permits from the DNR; as of now, one has been granted, one has been pending for an unusual length of time, and no other applications have been filed.

Mazour said a coalition has formed of many varied groups in opposition to the pipeline including farmers, environmentalists, elected officials, indigenous tribes and persons of both major political parties. People of all demographic groups oppose use of eminent domain, with a Des Moines Register about a year ago showing 78 percent of Iowans oppose it.

The goal of Sierra Club and other opposition groups is to make the approval process take as long and cost as much as possible.

Opposition activities have included encouraging board of supervisors in affected counties to submit formal objections to the Iowa Utilities Commission. Greene County filed one against Phase One and the supervisors have directed county attorney Thomas Laehn to draft an objection to Phase Two. Counties can also pass zoning ordinances to make siting a pipeline difficult.

Many people who attended the Aug. 8 meeting own property in the proposed route for Phase Two. Mazour instructed them that they can refuse acceptance of the 10-day restricted certified letter notifying them surveyors will be on their property. Surveyors can not enter a person’s property without permission. They can also request the pipeline company to get an injunction from a judge to allow the survey to occur. Landowners who have already accepted the letter can follow the surveyor as he/she works, take pictures or videos of the survey process, ask questions of the surveyor, or even ask a judge for an injunction against the survey.

Mazour encouraged all Iowans to file an objection with IUC. An objection can be one sentence or several paragraphs. Objections can be submitted at https://efs.iowa.gov.submit/comment

Northern Greene County landowner Dan Tronchetti is fighting Summit on Phase One. He spoke at the Aug. 8 meeting.

He said his first thought after learning his farmland was on the route was that he had spent tens of thousands of dollars on drainage tiles, as his land is not productive without the drainage. The top of the pipeline would be installed four feet from the soil surface, cutting through his drainage tile. Summit told him the company would repair his tile if it were damaged, but he fears it would not be a good repair. He also thinks that in the future no private tiling company would come near the area knowing there was a CO2 pipeline there.

He noted that a natural gas pipeline runs at 900 psi; a CO2 pipeline runs at 2100 psi. He said he thinks there’s no guarantee a CO2 pipeline won’t rupture.

He also said Summit has studies of where CO2 would go in the case of a rupture, but it refuses to share that information with landowners. He also said Summit has offered equipment and training to emergency responders that may have to deal with a rupture. Summit’s direction to responders is to barricade roads to keep people from leaving or going into the affected area; there is no training in assisting people within the “kill zone,” and responders are not to enter. “If you’re in the kill zone, you’re on your own,” Tronchetti said.

Tronchetti has been aware of Summit’s intentions since Aug. 2021. He said his objections have evolved in that time and have settled in two primary areas; the first is the use of eminent domain; the second is the amount of water used to compress the CO2 gas to a liquid.

Tronchetti’s presentation was followed by a Q & A time. The first question was about Department of Natural Resources water use permits. Mazour said permits are granted for a “beneficial use,” leaving the question of whether carbon capture in this amount is a beneficial use.

However, Masour pointed out that Bruce Rastetter, owner of Summit Carbon Solutions, has donated “a ton of money” to Gov Kim Reynolds, who appoints the DNR director. “We’re having a lot of trouble with agencies like the DNR and the Iowa Utilities Commission because they’re appointed positions, not elected positions,” she said.

A question came up about whether Summit would need permission to work within drainage districts. Greene County supervisor Dawn Rudolph noted that the tiles are owned by drainage districts, with the supervisors serving as trustees. County attorney Thomas Laehn said the county has the ability to require Summit to enter into a drainage protection agreement with each of the affected drainage districts. The supervisors have statutory power to put conditions on those agreements, but they don’t have the authority to stop a project. He said the county engineer would receive permit requests for crossing county roads.

Greene County farmer and activist George Naylor shared that ethanol plants create CO2 in two ways; first, from the fermentation of corn to create alcohol; and the second, from the energy required to run the plant. Summit would capture CO2 from only one of those processes, capturing only 0.2 percent of the total CO2 produced.

Another attendee suggested that ending the tax credits for CO2 capture would end the problem. He then asked exactly what defines “eminent domain.” Mazour answered that in Iowa, the test is that it must be “a public convenience or necessity.” Summit claims the pipeline is a necessity because of climate change and the importance of corn/ethanol to Iowa’s economy.

In the 2023 legislative session, the Iowa House passed a bill requiring that 90 percent of affected landowners must sign a voluntary easement before eminent domain can be used. The Iowa Senate did not take up the bill.

Summit Carbon Solutions will hold a required public informational meeting Wednesday, Aug. 28, at 12 pm at Clover Hall on the Greene County Fairgrounds in Jefferson. Henning encouraged persons who oppose the pipeline to attend the meeting wearing red, the rallying color of the opposition.